Posts tagged idris

So... HomeLab-2? What is that?

18 October 2023 (homelab programming retrochallenge retrochallenge2023 retro javascript idris)I don't blame you if you don't know what a HomeLab-2 is. Up until I listened to this podcast episode, I didn't either. And there's not much info online in English since it never made it out of Hungary.

As interesting as the history of this "Soviet bloc Homebrew Computer Club" machine is, I will be skipping that here and concentrate on the technical aspects.

Basic architecture

HomeLab-2 is a home computer in the eighties sense: a computer that boots to a BASIC interpreter, with a built-in keyboard, video output that can be connected to a TV.

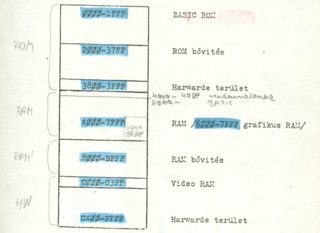

The core of the machine is the well-known Zilog Z80 CPU, one of the stars of this class of computers (the other one being, of course, the MOS 6502). It is connected to 8 KB of ROM containing the BASIC interpreter, some IO routines for thing like loading programs from cassettes, and a rudimentary monitor. The system also comes with 16 KB of general purpose RAM (upgradeable to 32 KB), and 1 KB of text-mode video RAM coupled with a 2 KB character set ROM that is inaccessible to the CPU.

One interesting aspect of the machine is that due to export restrictions and a weak currency, availability of more specialised ICs was limited, and so the HomeLab-2 was designed around this limitation by only using 7400-series ICs beside the Z80. This meant that a lot of the functionality that you would expect to be done with custom circuitry, chief among them the video signal generation, was done by the CPU bit-banging the appropriate IO lines. This is somewhat similar to the ZX80/81 video generator, in that the CPU "jumps" to video memory so that its program counter can be used as the fastest-possible-updating software counter, and the supporting circuitry makes sure the CPU's data lines are fed NOPs. Concretely, the value appearing on the data bus is 0x3F, which is effectively a NOP (it inverts the carry flag) and makes it easy to conditionally change it to a 0xFF, i.e. a RST 38, which is used to mark end-of-(visible)-line.

To program the HomeLab-2, you don't need to know the exact details of this, but it is important to keep in mind that as long as the video system is turned on, the CPU will spend 80+% of its time drawing the screen, leaving your program with less than 20% of its 4 MHz speed.

Data storage is done to cassette tape, via an audio mic/speaker port. Writing to a specific memory location sets the audio output into its high level for about 10 μs. The on-tape format is based on simple 10 μs-wide square waves 1.6 ms apart: for high bits, this interval is halved by an extra mid-point square. Of course, for the CPU to be able to accurately keep track of the audio signal timing, the video system has to be turned off while accessing the tape.

The audio output is also routed to an internal speaker so you can generate sound by modulating this 10 μs square.

The emulation sitch

To get started with HomeLab-2 development, we need some way of testing programs. A straightforward tool of doing that is an emulator of the machine. Unfortunately, at least back in August when I started working on my games, the emulator situation wasn't quite rosy.

The obvious place to check first is MAME, and indeed it claims to support the HomeLab-2. However, it was obviously written as a quick hack by someone who didn't really invest the time into understanding how the original machine's video system worked. This of course wreaks havoc with the timings, and makes it impossible to get cassette IO working.

Discounting very old emulators running on DOS, the other one I found was Attila Grósz's emulator of the whole HomeLab family, which had an update as recently as May 2022, but its HomeLab-2 support was quite limited. And much more annoyingly, it's a Windows-only closed source software. I don't want to dunk on the guy, but that's just stupid; especially because looking at the source of actual working emulators is usually a really good way in resolving any ambiguities in documentation during development. And realistically, what benefit can you possibly hope from your closed-source emulator of a computer that in our Lord's year of 2023 probably interests about a dozen people?!

So I did what any responsible adult would do when faced with a limited-time game jam where he has to also learn Z80 assembly and figure out, well, everything: I set out to put all that aside and cobble together my own emulator. With blackjack and hookers, of course.

My first emulator

Oops I guess the section title is a spoiler.

I wanted to make something that people can just use without any fuss, so I decided to target web browsers and make it into a single-page app. The goal was to quickly get something off the ground, publish it so that others can also use it for the game jam, and then later hope for contributions from people who know the machine better.

Because I was in peak "just get the damn thing working" mode, I decided to write vanilla JavaScript instead of transpiling from some statically typed functional language, which is what I would normally do. With JavaScript, at least I knew that whatever happens, the code might end up as a horrible mess of spaghetti but at least I won't run into situations where I'm "the first guy to try doing that" and everything breaks, which is usually how it goes with these projects of mine.

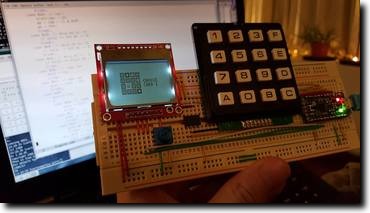

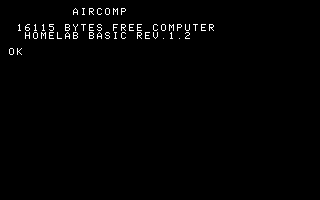

For the CPU core itself, I found an easy-to use Z80 emulator library. I connected it to some array-backed ROM and RAM, started rendering the text video RAM onto a canvas, and let the firmware rip. This got me all the way to the BASIC prompt, not bad for a couple minutes of hacking:

Getting from this to actually blinking the cursor and accepting input was much trickier, however. Remember all that detail a couple paragraphs ago about how the video system is implemented, what fake read values appear on the data bus as the video memory is scanned, that sort of stuff? That was not documented at all. The users' manual only mentions that the NMI "can't be used" for user purposes because it is used by the video system. I pieced the rest together mostly from reading the firmware disassembly, observing the CPU's behaviour, looking at the schematics, and doing a lot of "now if I were designing this machine, how would I do things?".

Eventually I got enough working that text-mode video worked; and then I gave up on raster video because I knew I wouldn't need it for the kinds of games I was envisioning. Then I added cassette IO, which necessitated a cassette player UI which then became way too much, and I kind of lost steam. But hey, at least I lost steam after I've got everything working. Well, everything except sound and raster graphics. But definitely everything that I was planning to use for my games!

This emulator, named HonLab (because HomeLab, and it runs on a web page, and honlap is Hungarian for home page, ha ha very clever, get it?! yeah sometimes I crack myself up!) can be used online here and its source code is on GitHub here.

Now, at this point, the game jam deadline was rapidly approaching, and I still haven't written a single line of Z80 assembly, so it was time to finally...

Writing a second emulator

Oh my god what is wrong with me.

Also, this blogpost is starting to take too long to write, so long story short: based on my previous good experience with Idris 2's JavaScript backend and also itching to use Stefan Höck's new SPA FRP library, I decided to write a new version from scratch (only reusing the Z80 core), but this time in Idris 2. It's almost as finished as the first version, just missing the ability to save to tape; you can look at its source here and it was exactly the kind of project that I initially wanted to avoid: one where a significant amount of my time went into reporting upstream bugs and even fixing some. Time enjoyed wasting, and all that.

Also, because the two emulators do look the same from the outside, I won't bother making another screenshot; you wouldn't notice it anyway.

So by the next post, we'll finally get to the beginning of September, when I started writing Actual Lines of Code.

A small benchmark for functional languages targeting web browsers

2 July 2022 (programming haskell idris javascript)I had an idea for a retro-gaming project that will require a MOS 6502 emulator that runs smoothly in the browser and can be customized easily. Because I only need the most basic of functionality from the emulation (I don't need to support interrupts, timing accuracy, or even the notion of cycles), I thought I'd just quickly write one. This post is not about the actual retro-gaming project that prompted this, but instead, my experience with the performance of the generated code using various functional-for-web languages.

As I usually do in situations like this, I started with a Haskell implementation to serve as a kind of executable specification, to make sure my understanding of the details of various 6502 instructions is correct. This Haskell implementation is nothing fancy: the outside world is modelled as a class MonadIO m => MonadMachine m, and the CPU itself runs in MonadMachine m => ReaderT CPU m, using IORefs in the CPU record for registers.

The languages

Ironing out all the wrinkles took a whole day, but once it worked well enough, it was time for the next step: rewriting it in a language that can then target the browser. PureScript seemed like an obvious choice: it's used a lot in the real world so it should be mature enough, and with how simple my Haskell code is, PureScript's idiosyncracies compared to Haskell shouldn't really come into play beyond the syntax level. The one thing that annoyed me to no end was that numeric literals are not overloaded, so all Word8s in my code had to be manually fromIntegral'd; and, in an emulator of an eight-bit CPU, there's a ton of Word8 literals...

The second contender was Idris 2. I've had good experience with Idris 1 for the web when I wrote the ICFP Bingo web app, but that project was all about the DOM manipulation and no computation. I was curious what performance I can get from Idris 2's JavaScript backend.

And then I had to include Asterius, a GHC-based compiler emitting WebAssembly. Its GitHub page states it is "actively maintained by Tweag I/O", but it's actually in quite a rough shape: the documentation on how to build it is out of date, so the only way to try it is via a 20G Docker container...

Notably missing from this list is GHCJS. Unfortunately, I couldn't find an up-to-date version of it; it seems the project, or at least work on integrating with standard Haskell tools like Stack, has died off.

To compare performances, I load the same memory image into the various emulators, set the program counter to the same starting point, and run it for 4142 instructions until a certain target instruction is reached. To paper over the browser's JavaScript JIT engine etc., each test runs for 100 times first as a warm-up, then 100 times measured.

Beside the PureScript, Idris 2, and GHC/Asterius implementations, I have also added a fourth version to serve as the baseline: vanilla JavaScript. Of course, I tried to make it as close to the functional versions as possible; I hope what I wrote is close to what could reasonably be expected as the output of a compiler.

Performance results

The following numbers come from the collected implementations in this GitHub repo. The PureScript and Idris 2 versions have been improved based on ideas from the respective Discord channels. For PureScript, using the CPS-transformed version of Reader helped; and in the case of Idris 2, Stefan Höck's changes of arguments instead of ReaderT, and using PrimIO when looping over instructions, improved performance dramatically.

| Implementation | Generated code size (bytes) | Average time of 4142 instructions (ms) |

| JavaScript | 12,877 | 0.98 |

| ReasonML/ReScript | 27,252 | 1.77 |

| Idris 2 | 60,379 | 6.38 |

| Clean | 225,283 | 39.41 |

| PureScript | 151,536 | 137.03 |

| GHC/Asterius | 1,448,826 | 346.73 |

So Idris 2 comes out way ahead of the pack here: unless you're willing to program in JavaScript, it's by far your best bet both for tiny deployment size and superb performance. All that remains to improve is to compile monad transformer stacks better so that the original ReaderT code works as well as the version using implicit parameters

To run the benchmark yourself, checkout the GitHub repo, run make in the top-level directory, and then use a web browser to open _build/index.html and use the JavaScript console to run await measureAll().

Update on 2022-07-08

I've added ReScript (ReasonML for the browser), which comes in as the new functional champion! I still wouldn't want to write this program in ReScript, though, because of the extra pain caused it lacks not only overloaded literals, but even type-driven operator resolution...

Also today, I have received a pull request from Camil Staps that adds a Clean implementation.

Hacks of 2015

28 December 2015 (programming haskell idris javascript games electronics avr fpga meta)Encsé writes in his blog that one of the reasons he created a tiny CPS-based Scheme interpreter was because he realized he hasn't done any fun side projects all year. So I thought I'd make an inventory of fun hacks I've done in 2015.

Bit-fiddling

- An FPGA implementation of the Commodore PET. This is still not fully finished: although I managed to hunt down the bug mentioned at the end of the blog post, I still haven't gotten around to implementing Datasette (tape) I/O.

- Viki & I put together a prototype for an AVR-based CHIP-8 handheld. This one has no web presence yet; we're hoping to finalize the design into a PCB-based one, before releasing the schematics and the code.

- Went to a hackerspace.sg workshop/hackathon for the Fernvale platform. Not much came out of that, I think I was the only person who at least got as far as running my own code on the device (reusing the low-level bitbanging from Fernly of course). I ended up doing some lame but colourful animations on the screen that would have gotten me boo'd off the stage in a 1986 demo compo.

Games

- I wanted to do some old-school 8-bit hacking, and ended up reverse-engineering and then reimplementing in Inform 6 the classic Hungarian text adventure game Időrégész. This even got me my fifteen minutes on Hungarian retro-gaming blog IDDQD.

- I managed to convince Viki to join me in participating in MiniLD #56. We decided early on to go with only 2 keyboard keys, 4 colours, one game mechanic, and a dancing theme — so, a rhythm game! To make deployment easy, we wanted it to be playable via just a web browser, and ended up choosing Elm as our development platform. The end result, after a frantic weekend of hacking, is Two-Finger Boogie.

Talks

- I gave an introductory talk on Kansas Lava first at Haskell.SG and then again at FP-BUD while visiting friends & family back in Hungary.

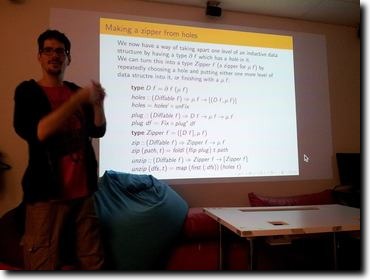

-

Presented McBride's seminal

paper on zippers (that was sadly never published AFAIK) at

Papers We

Love's Singapore chapter (slides and Haskell implementation

available here).

- Back in October, the self-interpreting in Fω paper started making huge waves in PLT circles. I was only three pages in when I knew I had to present it at Papers We Love. The eventual talk took a couple weeks to prepare for, but it was worth it because it went really well.

Functional programming

- Fixed a long-standing bug in MetaFun, the "Haskell"-to-C++ template metaprogram compiler: patterns in function definitions are now tried for matching in the correct order.

- Wrote a Bison summary parser that a co-worker wanted to use to generate exhaustive test cases for Bison-generated parsers. That project ended up not going anywhere as far as I know.

- If you use every GHC extension and then some, you can write a fairly nifty untyped-to-typed embedding of STLC that is almost as nice as doing it in a proper dependently typed language!

Stack Overflow highlights

Some of the answers I wrote this year on Stack Overflow required me to learn just enough of something new to be able to answer the question:

- Learned just enough about Uniplate to figure out how to do out-of-band code generation.

- Learned just enough about Persistent to figure out how entity keys are represented on SQL database backends.

- Learned just enough about Spock to figure out how to store state between handler invocations (spoiler alert: it's horrible).

- Learned just enough about data-reify to figure out how to observe sharing in a graph

- Learned just enough about Pipes to figure out not just how to generalize runEffect, but also a way to get notified about the end of the input.

- Learned just enough about Accelerate to figure out marshalling of Arrays.

- Learned just enough about Template Haskell to figure out how to create and use custom annotations. OK, so maybe this isn't strictly true, as Template Haskell is something I've known already, but the annotations stuff was definitely new.

- Learned just enough about Euterpea, and the Karplus-Strong algorithm, to figure out how to synthesize a plucked string-like sound out of thin air and white noise.

- Learned just enough about GHCJS to figure out how unboxed Vectors can be efficiently marshalled to Javascript.

- Learned just enough about GHC's RULES facility to figure out how to wrangle it to submission when rewriting overloaded functions.

- Learned just enough about LLVM and GHC's run-time system to figure out how to present handwritten LLVM assembly to GHC as a prim-op.

Then, there were those where it turned out there was a bug to be found by scratching the surface of the question deep enough:

- I've found a bug in Idris's typechecker in the face of typeclass polymorphism

- Even though Tardis and rev-state should be mostly the same code (and they are even written by the same developer!), the latter's MonadFix instance had a one-character, fatal flaw.

Then there were the answers that were just too much fun to write:

- A small romp in integer arithmetic to implement rational addition in Agda

- Reimplementing Parsec in Idris because I was too lazy to look into Lightyear.

- What is the codensity-like representation of MonadPlus? This paper answers the question by wonderfully building up a generalization of DList and Codensity for something which is almost MonadPlus. I ended up writing a summary of the paper.

- Having worked on GHC two years ago to implement pattern synonyms, with the understanding of GHC's type checker internals still fresh in my mind, I was just the right person to explain the GHC code base's usage of the word zonking.

All in all, it seems this has been quite a productive year for me out of the office, even if you exclude the Stack Overflow part. I was actually surprised how long this list was while compiling it for this blog post. Maybe I should write a list like this every year from now...